Visual repatriation is, in many ways, about finding a present for historical photographs, realizing their potential to seed a number of narratives through which to make sense of the past in the present and make it fulfill the needs of the present.

(Elizabeth Edwards)

***

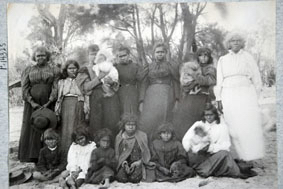

“Group of Aboriginal women and children. The children are sitting, while the older women are standing. The women are all wearing long-sleeved long dresses or long skirts and blouses. There are trees in the background.” Photo originated in Daisy Bates Collection. Accession #14325

Traditionally, Aboriginal people recorded their history orally and were able to keep alive the memories of loved ones and the knowledge of country without the necessity of the written word or archival record. Since colonisation however, people’s oral histories in many places have become fragmented. With access to relevant photographic collections, Indigenous people/communities today are able to amalgamate the archival image with their oral histories. As a result, the concept of time becomes somewhat blurred whereby the past, present and future co-exist in the here and now. Not only do they depict images of people’s ancestors, their country and places of significance, but they become ‘living entities’ in their own right – able to remove themselves from the spectrum of time and the Western concept of ‘the past’ and place themselves within the ‘here and now’.

In the past, Indigenous interaction with Institutions like museums and state government run libraries and departments have been limited and one sided. In many cases Indigenous peoples had become the object and subject of archival collections –collected and archived through the eyes of the non-Indigenous outsider. However, with greater access to resources that allow Aboriginal communities greater agency, the process of reconciling aspects of the past can begin. With Aboriginal peoples now looking back at these institutions through the looking glass (so to speak), the relationship between institutions and Aboriginal people can be based upon a more equal footing.

“Group of Aboriginal women and children. The children are sitting, while the older women are standing. The women are all wearing long-sleeved long dresses or long skirts and blouses. There are trees in the background.” Photo originated in Daisy Bates Collection. Accession #1998.249.12.3

Finally, with access to these images, we as Indigenous people are able to come full circle – what was then has become the now. For many today, finding and receiving images of one’s ancestors may be the only link people have to their pasts. It is especially relevant for members of the Stolen Generations who were forcibly removed from their families and cultural heritage. Thus, they are able to begin a healing process and find – for want of a better term – an ‘end in the beginning’. It is also rewarding to be a part of a process that can also bring so much joy to many Indigenous families and communities who are able to view images of their ancestors long since departed. What was once a research tool used to “study” Aboriginal peoples, the photographic archive has now become an amazing window into our pasts.