Dr Chris Morton, project partner

This is a story about one of the most colourful characters to emerge from the research process as part of this project. The story centres on the mysterious figure of Julius Ferdinand Berini, a Swiss or German immigrant to Australia in the early 1860s, and whose significance has been completely overlooked in histories of early photography collecting in Australia.

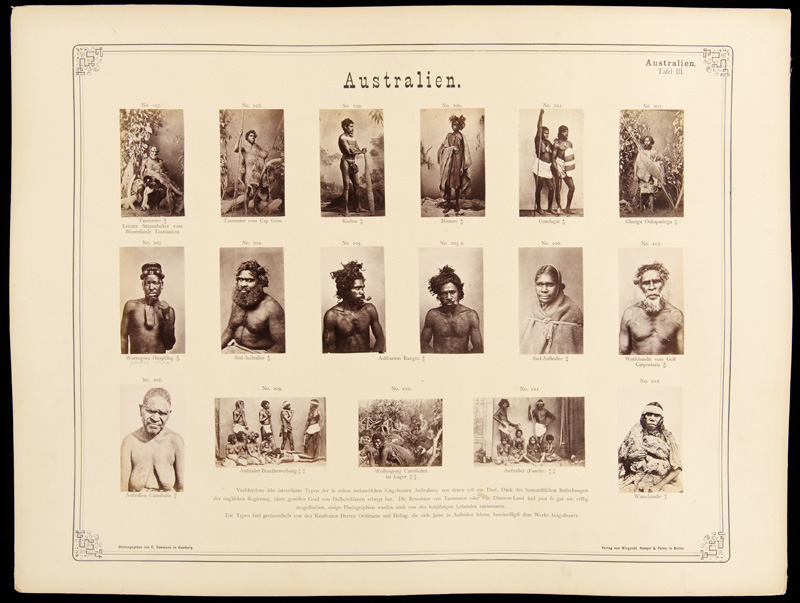

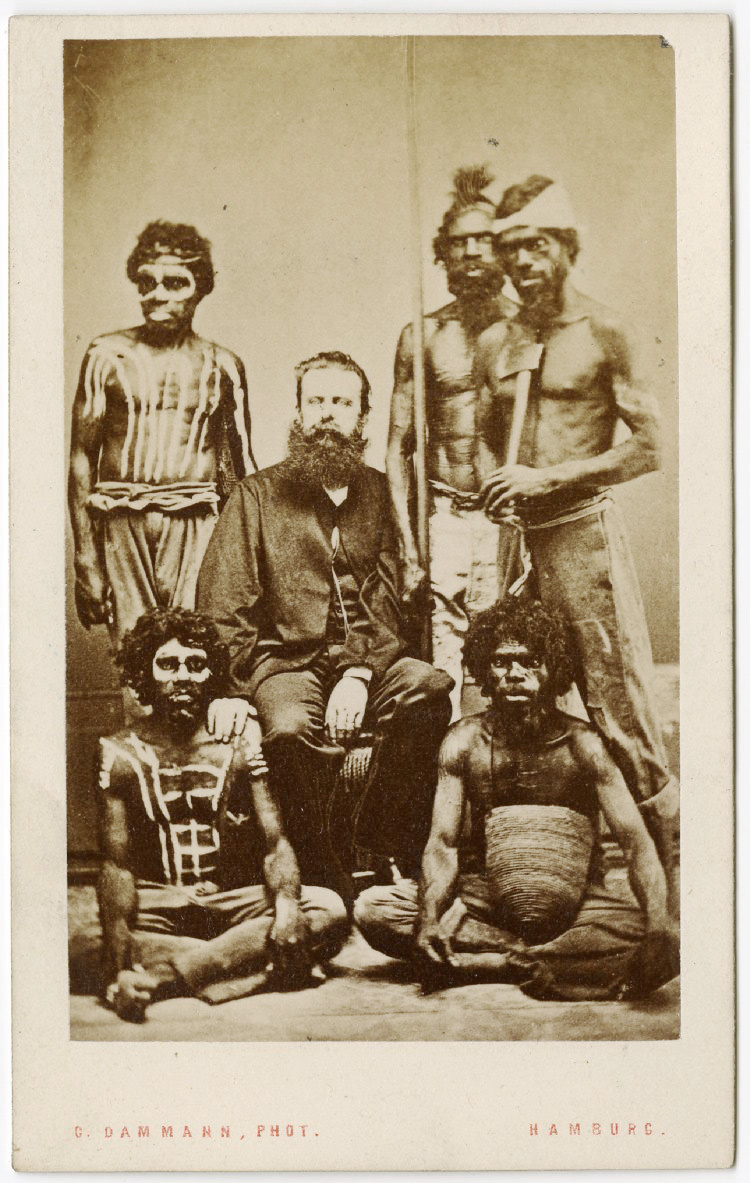

Australien’, Table 3 from C. Dammann’s Anthropologisch-ethnologisches Album, 1873-6, which contains imagery mostly supplied by Berini, including one purportedly of a man from Warrego, Queensland (centre row, left), but is clearly a Zulu from South Africa. Radcliffe Science Library, University of Oxford.

The importance of Berini emerged during my conversations with a German colleague Thomas Theye, who has spent many years studying the work of the German studio photographers Carl and Frederick Dammann, and in particular their magnum opus Anthropologisch-ethnologisches Album which was published in folio format between 1873 and 1876. The Album contains 50 folios containing hundreds of photographs of peoples from around the world, all copied from originals collected by the Dammann studio, or sent to it by the Berlin anthropology society who initiated the project.

Now, whilst the details of the Dammann publication are fairly well known, little research has so far been done on the sources (collectors) and photographers themselves, whose work was copied by the Dammann studio in Hamburg in the mid 1870s.

The Pitt Rivers Museum is probably the best archive of Dammann material in the world since it bought the residue of the project from the estate of Frederick Dammann in 1901, including many of the copy negatives and loose prints.

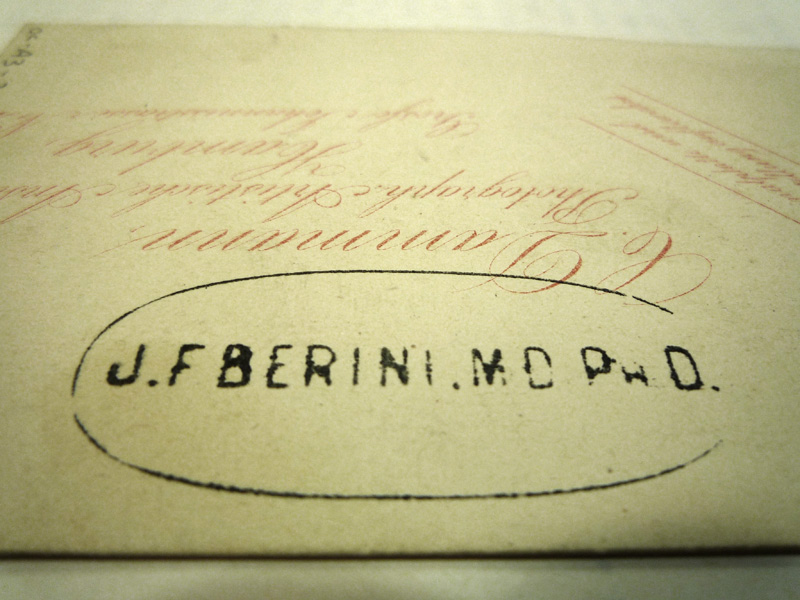

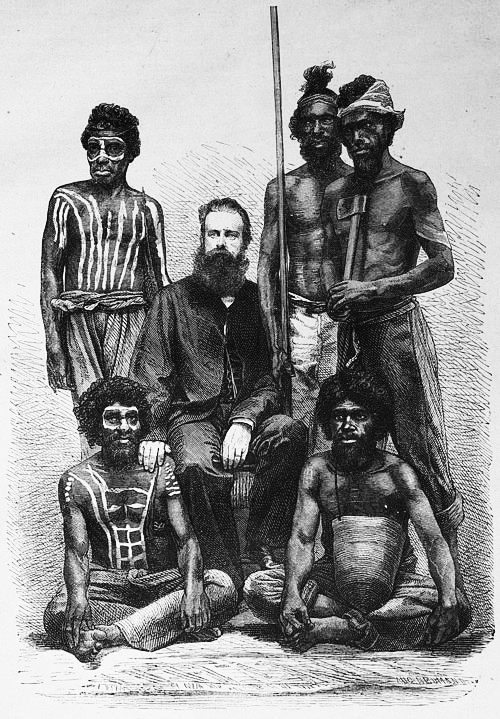

In the summer of 2011 as the project was getting underway, Thomas Theye and I paid a visit to the British Museum to examine early Australian photographs held there. In one album there were a number of Dammann copies, and 18 of them had the name ‘Dr Berini’ noted on the reverse, making Berini Dammann’s most significant source of early Australian imagery. But just who was Dr Berini, and what was his significance? One important photograph also leapt out, being a studio portrait of a white man surrounded by a number of indigenous men. On the back was Dammann’s usual studio printed design, along with another stamp ‘Julius Berini MD PHD’. Did this portrait show the mysterious Dr Berini?

Portrait of Julius Ferdinand Berini with five indigenous men, taken in Brisbane, probably in 1868. British Museum collection (oc-a3-33)

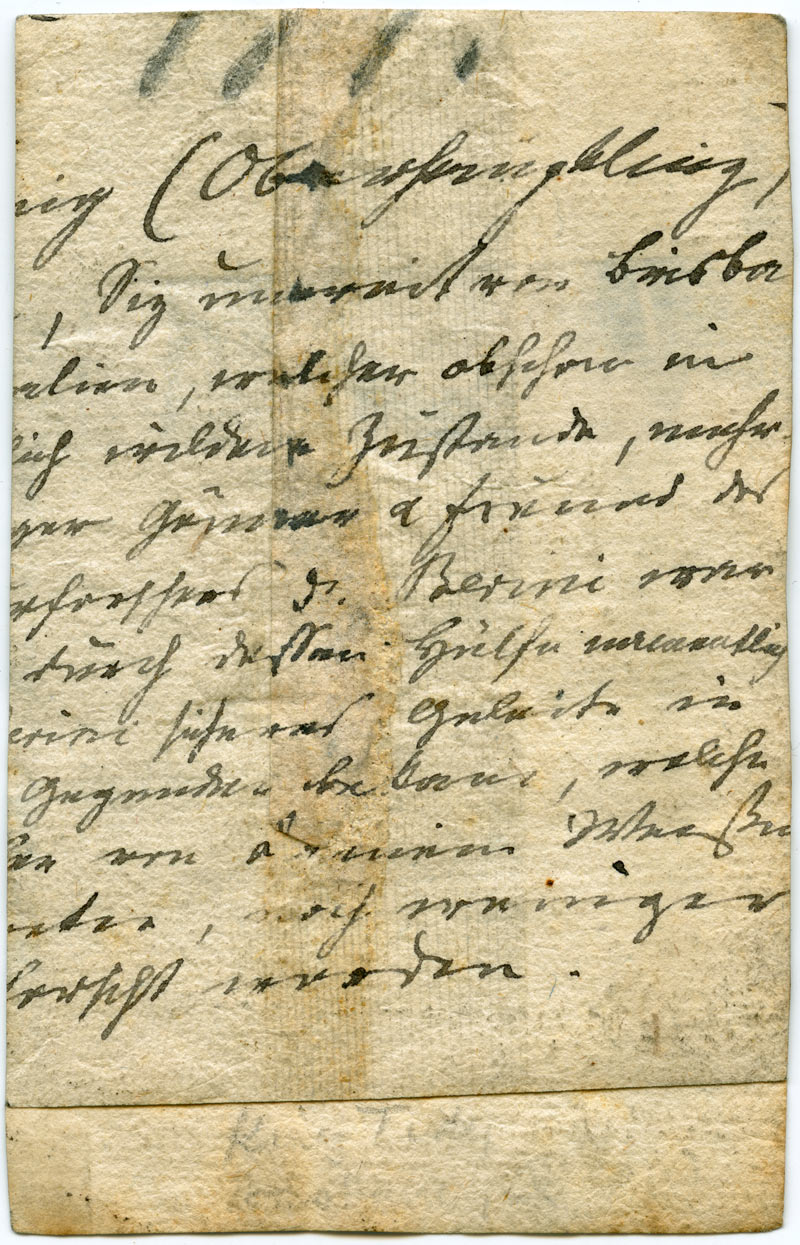

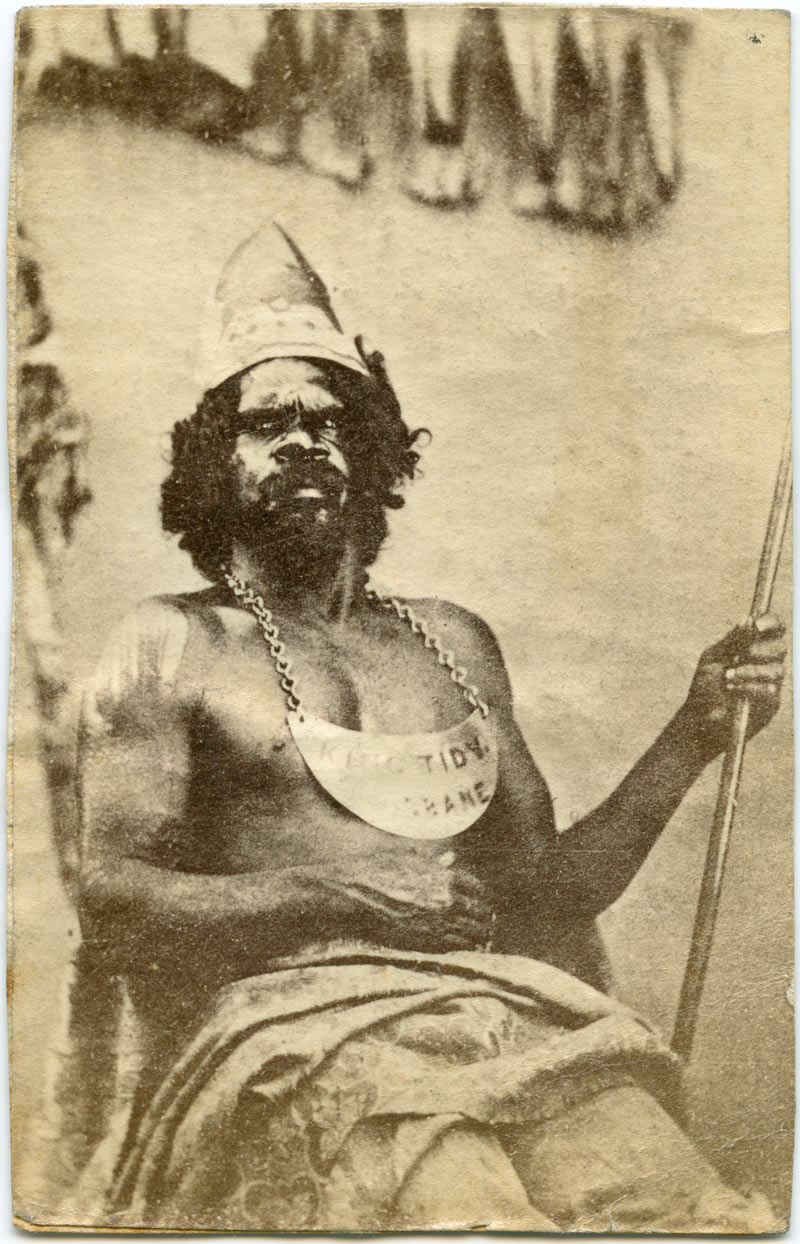

A further clue came when Thomas Theye and I went through the Australian Dammann copies at the Pitt Rivers Museum. On the reverse of a carte-de-visite portrait showing ‘King Tidy’ of Brisbane was a cropped note in German, which reads roughly in English:

King (Chief), living not far from Brisbane, Australia, who although in an entirely savage condition was a patron and friend to the natural scientist Dr Berini on several occasions. He gave Berini particularly a secure escort on his way to areas never before explored or entered by a white man.

It is unclear who wrote this inscription, but it may be that that it was whoever sent this print to Dammann for copying, perhaps someone at the Berlin Anthropology Society, so that he would have the relevant information to publish alongside it.

Portrait of ‘King Tidy’ of Brisbane, c. 1868, collected by JF Berini. Pitt Rivers Museum (1998.307.387)

In early 2012 I began to see what I could find out about the mysterious Dr Berini. The first piece of evidence came in the form of an 1868 article entitled ‘Ein deutscher gruss von Australien her’ in the magazine Die Gartenlaube. The article starts by recounting an accident that befell Berini and his wife in March of that year when their dog savagely attacked them. It then continues to reprint a rambling letter to the magazine that Berini had sent in January 1868 in which he discusses the indigenous men in the group portrait, which is also reproduced in engraved form.

Turning to the amazing resource of digitized Australian newspapers, an extraordinary and intriguing picture emerged. The first mention I found was in Grafton, NSW, in 1864, where a letter was sent to the editor of the Clarence and Richmond Examiner by one C. Zimmler, who was a chemist and druggist, complaining about Berini claiming the qualification MD when he is more than likely not qualified at all. This is a theme that continues. In 1865, in the same newspaper, a letter of resignation from the Grafton hospital was published from Berini and another man, citing rumours against them. Possibly as a result of this, Berini moved to Brisbane in November 1865 and advertised himself as a physician and surgeon, based at Kangaroo Point. A picture of a man charging heavy fees for services that have at best mixed results then emerges, and Berini pursues non-payers through the Brisbane courts. In 1868 comes the exciting incident of the dog attack. The Clarence Examiner reports that one evening Berini’s mastiff was let off his leash and set upon him, inflicting 23 deep wounds, and a further seven wounds on his wife Caroline who tried to help.

Berini’s attempts to extract money from his evidently unsatisfied patients seems to have precipitated a decision to leave Brisbane in 1869. The Brisbane Courier of 31 May carries the notice ‘Leaving Brisbane tomorrow, I wish to say to all my friends and enemies (if I have any) a hearty GOOD BYE. J.F.Berini MD. Advance Queensland!’ Berini’s departure from Brisbane provides a latest date for when the photographs he supplied Dammann from Queensland could have been taken, many of which have in any case been identified as the work of such studios as Daniel Marquis.

Berini settles in mid 1869 in the German town of Hahndorf near Adelaide in South Australia, and a note in the South Australian Register in August relates that it had recently been reported in the Clarence and Richmond Examiner that Berini and his wife had decided to leave Queensland due to the dog attack and their declining health, preferring the ‘salubrious and bracing air of South Australia, where Dr Berini contemplates following his favourite studies of the ‘Flora and Fauna’ of Australia’. This is presumably where his interest in the Indigenous population came in, and why he collected Aboriginal photographs.

Soon after this Berini begins to sue people for non-payment in the Adelaide courts, and in one case against a Mr Frame in 1871 he actually admits to not being a qualified doctor, which was printed in the report in the South Australian Register. The following month, sensing the damage to his reputation, Berini publishes an explanation in the newspaper, stating that ‘he wishes to explain that the reason he occupies such a position is that the Medical Board refuses to recognize Swiss diplomas. He received the degrees of Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Zurich, in which he studied for seven years.’ Conveniently, the originals of his certificates were not available, having for some reason been sent by Berini to London ‘for approval of the medical authorities there’.

It appears that the damage to Berini’s reputation in South Australia was as bad as it was in Brisbane however, since we next read in October 1871 in The Argus, Melbourne, that Berini is seeking an appointment there as a resident medical officer at the Alfred Hospital. His application letter states that although he has not yet been admitted as a legally qualified doctor in Victoria, he expects to be shortly, and asks for an apartment and a servant at the cost of the hospital. His application is deemed ineligible.

In August 1872 a sensational report in the Evening Journal (Adelaide) states that the discredited Berini has visited Europe, where he had entertained audiences with tales of travel in

‘Borneo, New Guinea and Fiji accompanied by a suite of five natives of Australia, three Mongols and two Malays; that he had several encounters with the natives of those islands, in which he received spear and tomahawk wounds; and that he had succeeded in making wonderful discoveries of and scientific observations of a highly interesting nature. His miraculous stories appear to have found belief at London and Berlin, for according to the latest accounts he has been received with enthusiasm. Those who have known Berini in this colony are well aware that he never visited those islands, nor ever had a ‘dark suite.’ Several authoritative accounts have been sent by the last mail to England and Germany, which will speedily stop the little game of that pseudo-explorer.’

It is clear that Berini was using his collection of Australian photographs as evidence of his exploits to his credulous audiences in Europe. The group portrait of Berini with five indigenous men surrounding him was, as we know, taken in Brisbane in 1868, probably at the Daniel Marquis studio. It is highly unlikely that Berini knew the Aboriginal men in the picture personally, despite what he says in the article in Die Gartenlaube and much more likely that the studio arranged it all for Berini. And surely the tales of spear wounds from natives are the wounds from his dog, inflicted on a hot night at home in Brisbane, rather than in Borneo or Fiji.

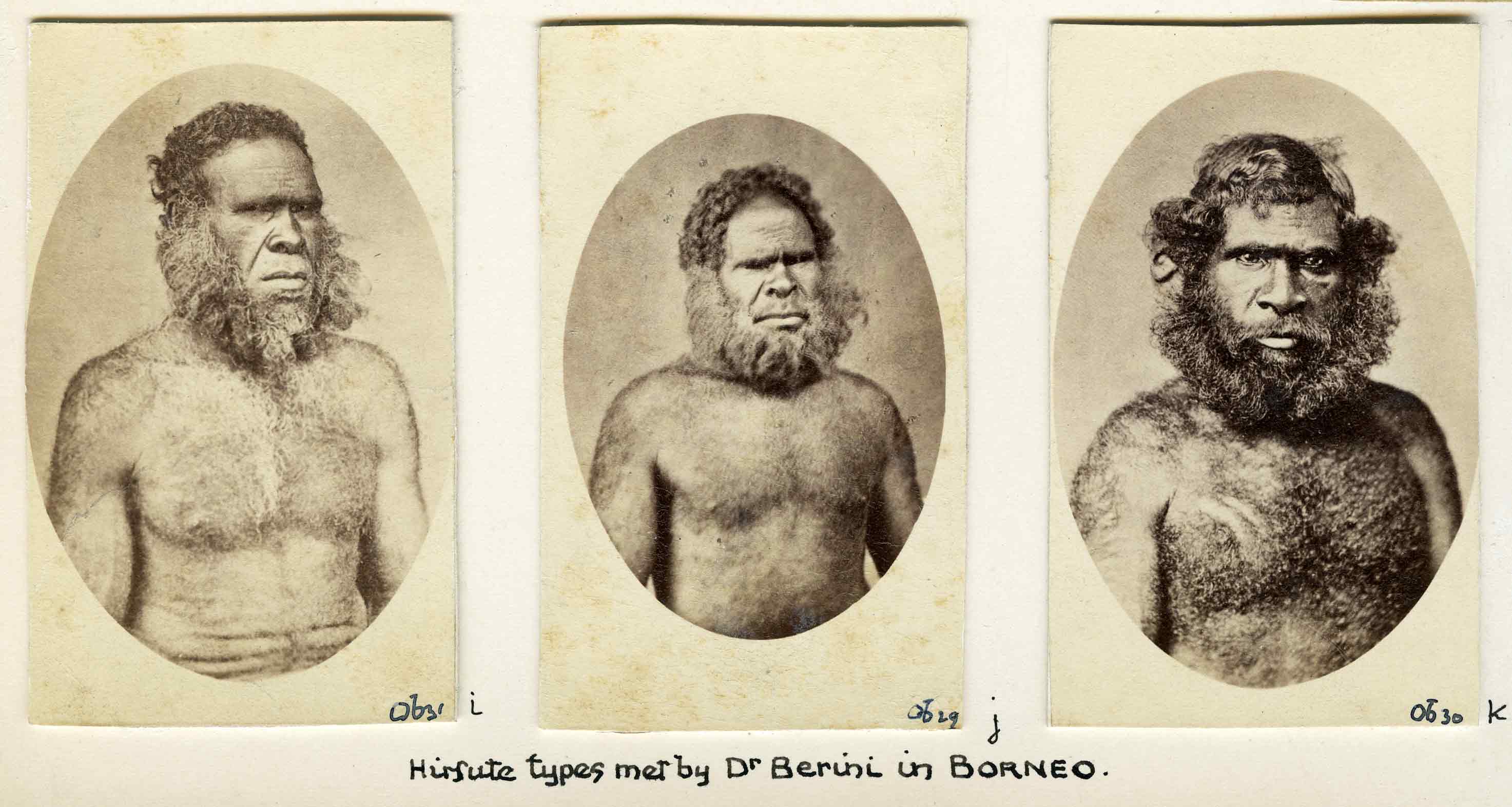

‘Hirsute types met by Dr Berini in Borneo’ – 3 portraits collected by Berini, probably in South Australia in the late 1860s. Pitt Rivers Museum (1998.229.11.9-11)

It was presumably during his documented visit to Berlin in 1872, where he presumably lectured to members of the anthropological community, that Berini’s photographs were eagerly requested by the Berlin Anthropology Society for their project to disseminate ethnographic images through publication, by the Dammann studio in Hamburg. Evidence that Berini used his photographs to back up his claims of adventurous travel can be found in some of the documentation passed on to Dammann with the photographs. Under three portraits in the Pitt Rivers Museum that were copied by Dammann is the caption ‘Hirsute types met by Dr Berini in Borneo’. It seems reasonably clear to me however that these men are likely to be from South Australia, and certainly not from Borneo. Nonetheless, Berini’s purported scientific qualifications and the statement that he had actually met them there presumably lent weight, not to mention the fact that in 1872 very few people in Europe had ever seen an indigenous person from either place.

Our final piece of information about the fate of Dr Berini comes in a short note some years later, in 1881, in The Argus (Melbourne), where it is reported that a man called Berini had recently been imprisoned in Switzerland for forgery, and during his trial he had produced a certificate purportedly from the Medical Board of Victoria, although there was ‘no such name appearing on the board’s register’. Berini’s trail then runs cold, at least for now, leaving behind a fascinating story of forgery, quackery, legal wrangles, tall tales and savage dogs.

Whilst it seems obvious that Berini was a charlatan, it is also clear that he had a genuine interest in the natural history of Australia and some aspects of Aboriginal culture. And as a result of his photographs having been copied by Dammann in Germany in the mid 1870s, Berini should now justly be considered as one of the most significant collectors and disseminators of early Australian Aboriginal photography to Europe.