24 July – 4 August 2017

John Ngatani, Jurpa Wurruamarra, Madi Murrungun (left to right) [RV-10532-A16-11A]

The National Museum of World Cultures in the Netherlands (an umbrella organisation located in Amsterdam, Leiden, Rotterdam and Berg en Dal) holds some 500 photographs made by the Dutch anthropologist Alexander van der Leeden during his one-year fieldwork research in Numbulwar in 1963-1964. The photographs give a snapshot of life in a settlement on the eastern coast of Arnhem some ten years after it had been founded. Indeed Numbulwar, or Rose River Mission by its original name, was established as a mission post in 1952 by the Church Missionary Society (CMS). The main goal was to provide the nomadic Nunggubuyu population with a settlement of their own.

Naming people

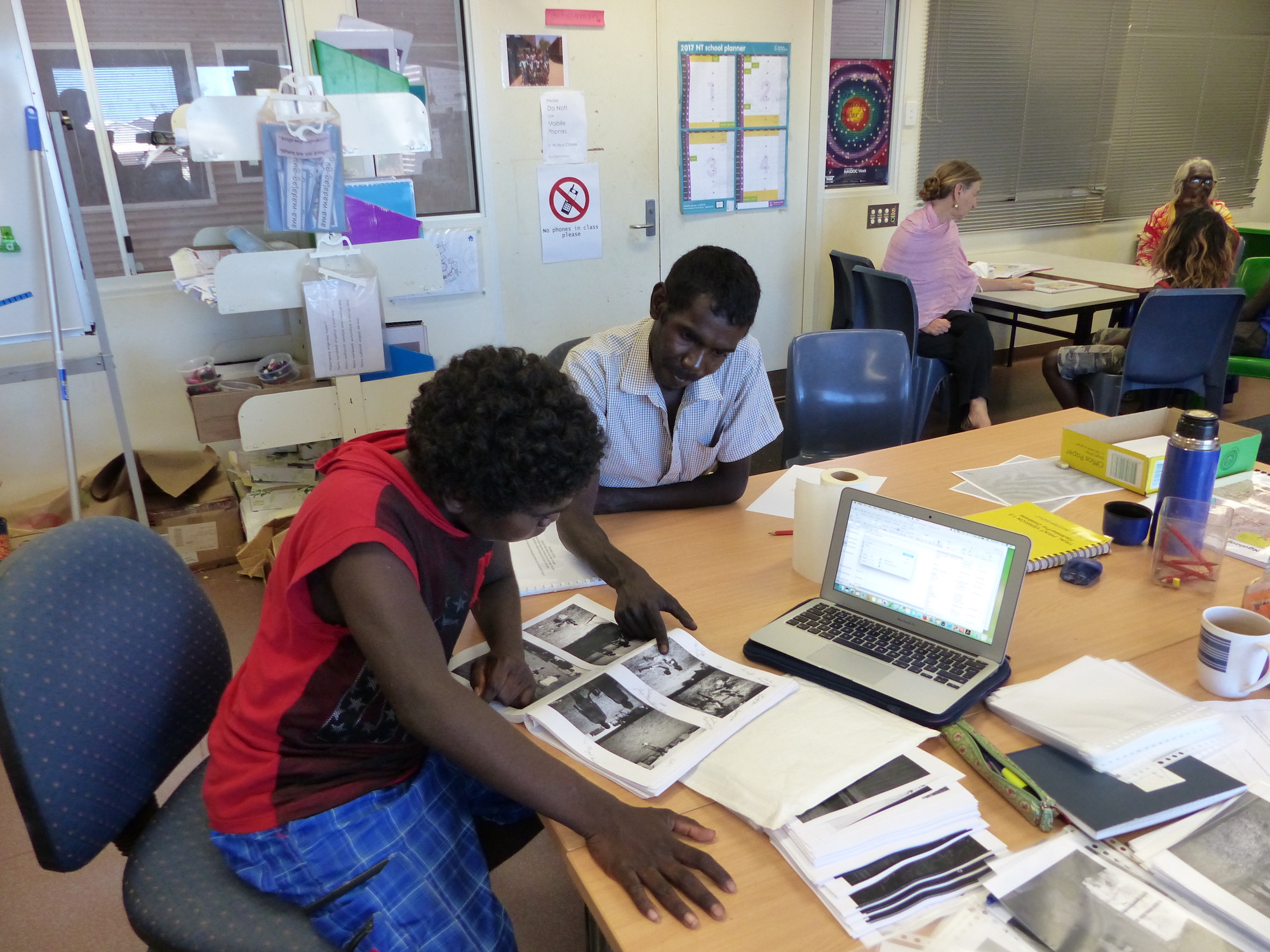

Paul Numamurdirdi and Hilda Ngalmi identifying people in the photographs.

The first step was checking the identification of people in the photographs and the spelling of their names. This work was done in collaboration with a few elders – both men and women – who could also advise on men’s ceremonial images. An excel spread sheet now compiles the photo number with the names of people and place appearing in the photograph.

The naming of people is especially important for the younger generations who might not know what their grandfathers and mothers look like, but do know their names. Even though some of the people in the images had recently passed away, the elders felt it important that I noted down their correct names as they realised this information would then be handed down to their children and grandchildren. Thus, when culture can be kept alive, a pragmatic approach was adopted towards cultural protocols and guidelines.

Exhibiting in the village

Wonu Veys laminating photo sheets

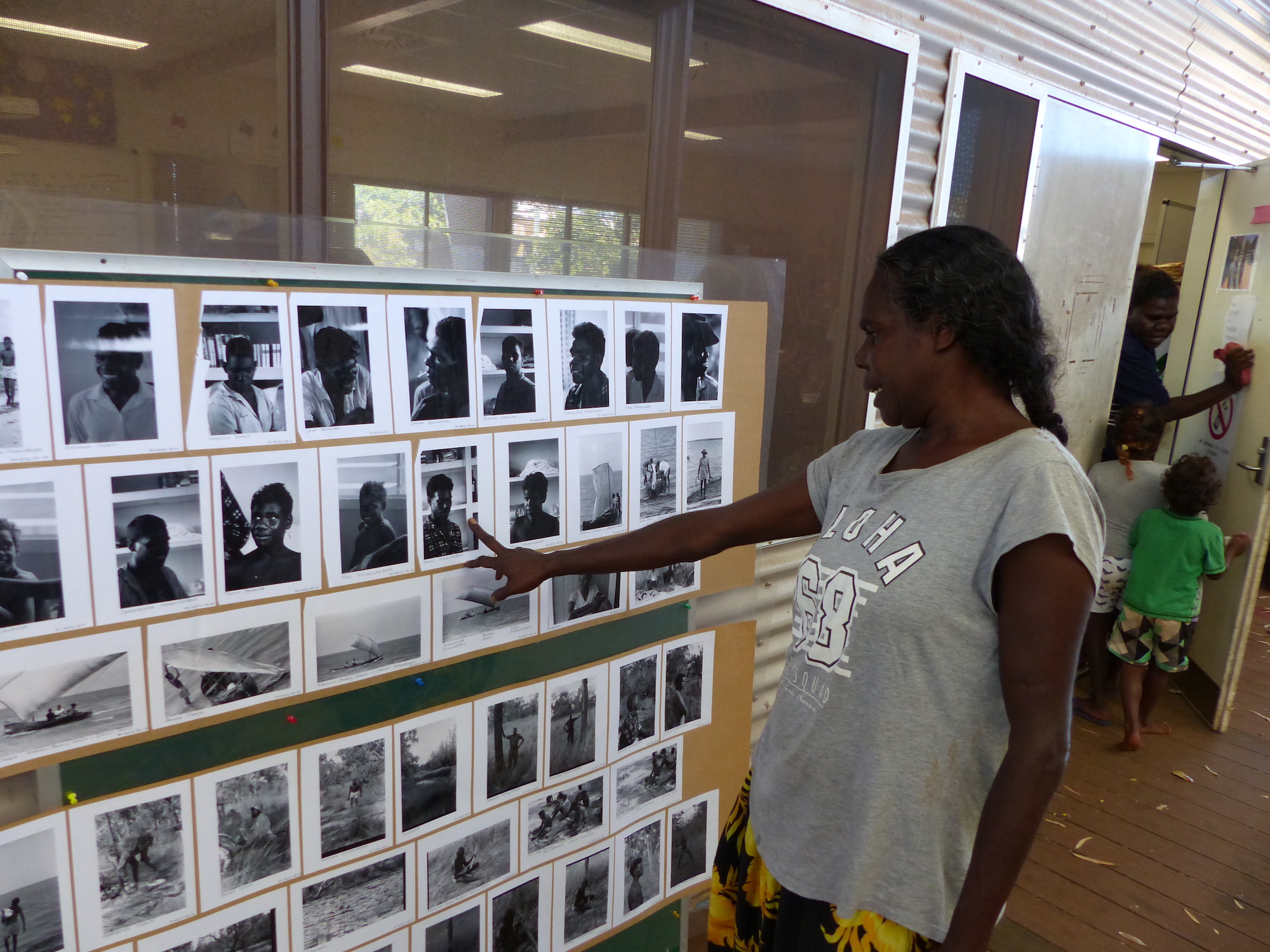

My workplace was the Wubuy language room in the Numbulwar school. While in the 1960s Wubuy was the main language of the inhabitants, today Kriol, a creolised language based on English, is the mother tongue for most children. However, Numbulwar has today an active programme of teaching Wubuy from preschool children to young adolescents. Together with the teacher linguists Jangu Nundhirribala, Hilda Ngalmi, and Helen Flanders we decided to paste the photographs, which I had printed on A5 formats, on large sheets of brown paper that were subsequently laminated. The 170 photographs on display had all the names of each individual person appearing in the photograph. The laminated sheets were put up just outside of the Wubuy classroom and outside of the Numbalwar shop.

People enjoying the exhibition at Numbulwar school.

People came in large groups or by themselves. The display appeared to be an intergenerational affair with children, young adults with their toddlers and elders attending. Some people came back several times or brought family members to come and see the exhibition. It allowed for everyone to reaffirm his or her kinship links. Most people spent at least half an hour in the exhibition.

People looking at the exhibition at the Numbulwar shop.

The versatility of the laminated rolls means that the exhibition will be easily set up at the Numbulwar Festival held in September 2017.

Teaching

Dan Bara explaining kinship relations to a school boy.

Paul Numamurdirdi wants to show the ceremonial images to boys in preparation for their circumcision ceremony that is planned around Christmas time this year. Several people in the community saw the photographs also as an important teaching tool. Photographs, which paid attention to didgeridoo making, or dugong fishing were popular. However, non-motorised canoes with sails attracted great interest. Some of the school children tried to play truant telling the teachers linguists that they needed a little bit more time to look at the images before going to their Wubuy class.

Hard copies in a digital age

Capturing images with the smart phone

Many people in the community have smart phones that they used to take pictures of single images. Moreover, the images are available on the school computers. Community members are actively looking for possibilities of granting access to these digital images in the newly built small arts centre. Despite all these digital access possibilities, the exhibition visitors appreciated the presence of physical prints making material engagement possible, touching and pointing at the images. Moreover the community members appreciated being able to get hard copy images featuring their family members, which were printed at the Numbulwar school. The sharing of images with Numbulwar community members showed the importance of having the actual images in the community while providing back-up access in digital format as well.

Engaging with the photographs

I am grateful to the Numbulwar school staff and all people connected to the school. Helen Flanders, Hilda Ngalmi, Dan Bara, Jangu Nundhirribala (in addition she took me fishing and catching crabs, and showed how to cook dugong), Paul Numamurdirdi and Anthony Gray have been particularly helpful in the process of naming people and facilitating the exhibition process.

Giningai Ngalmi recognising his portrait at the exhibition; RV-10532-A3-1

I am also indebted to Jane Lydon and Donna Oxenham at UWA for their intellectual generosity and allowing me to be part of the ARC funded project “Globalisation, photography, and race: the circulation and return of Aboriginal photographs in Europe”. Victoria Burbank with her decades of research experience in Numbulwar facilitated my initial steps in the community by suggesting people I could speak to. Last but not least, I want to thank the people of Numbulwar who welcomed the photographs (and me) with such an enthusiasm that once again proves the significance and relevance of sharing museums’ photographic archives with the community.