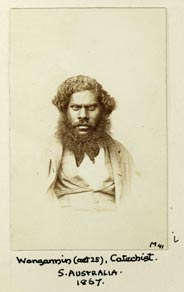

“Portrait of young Aboriginal man called James Wanganeen (1836–1871) in European coat, waistcoat, shirt and necktie. Plain studio background. James Wanganeen was a catechist or lay preacher at Poonindie mission.” Pitt Rivers Museum; Accession # 1998.249.33.9

The process of returning historical photographic collections to Aboriginal communities today is a complicated process. This is why it is fundamental that the process of returning photographic materials is handled in a culturally appropriate manner. Having personally worked with Indigenous visual and audio archival collections previously and been involved with the returing of photographs to communities – some of which contained culturally sensitive materials, it is important to fully understand the significance these compilations represent for Indigenous peoples.

It is often said that a photograph can speak a thousand words, but for Indigenous peoples these archival images represent so much more. Not only do they depict images of people’s ancestors, their country and places of significance, but they become ‘living entities’ in their own right – able to remove themselves from the Western concept of ‘the past’ and place themselves within the ‘here and now’.

By recording our histories within oral traditions, Indigenous peoples were able to keep alive the memories of love ones and the knowledge of country without the necessity of the archival record. Having said that however, with greater access to relevant visual collections, our Indigenous peoples and communities today are able to amalgamate the visual image with their oral stories and histories. As a result, the concept of time becomes somewhat blurred whereby the past, present and future co-exist in the here and now.

“Group of five senior Noongar men wearing European trousers, with ornate white paint on their bodies, faces, arms and legs. Left to right: Joobaitch, Woolber, Monnop, Dool and Genbursong.” Circa 1900; Source: Henry Balfour. Accession #1998.172.34.3

Many collections today are welcomed by the majority of Aboriginal peoples who see these records as evidence of their survival and strength, not as depictions of a ‘dying race’ or the colonised. What is more important to community members is the people, places of significance and country that can be found within these images. The photographic archive is a powerful source of information for Aboriginal peoples. In each image we see where we’ve been and in turn what we’ve become. They are ‘living’ proof that Aboriginal people are survivors and that our culture has survived through tremendous adversity.