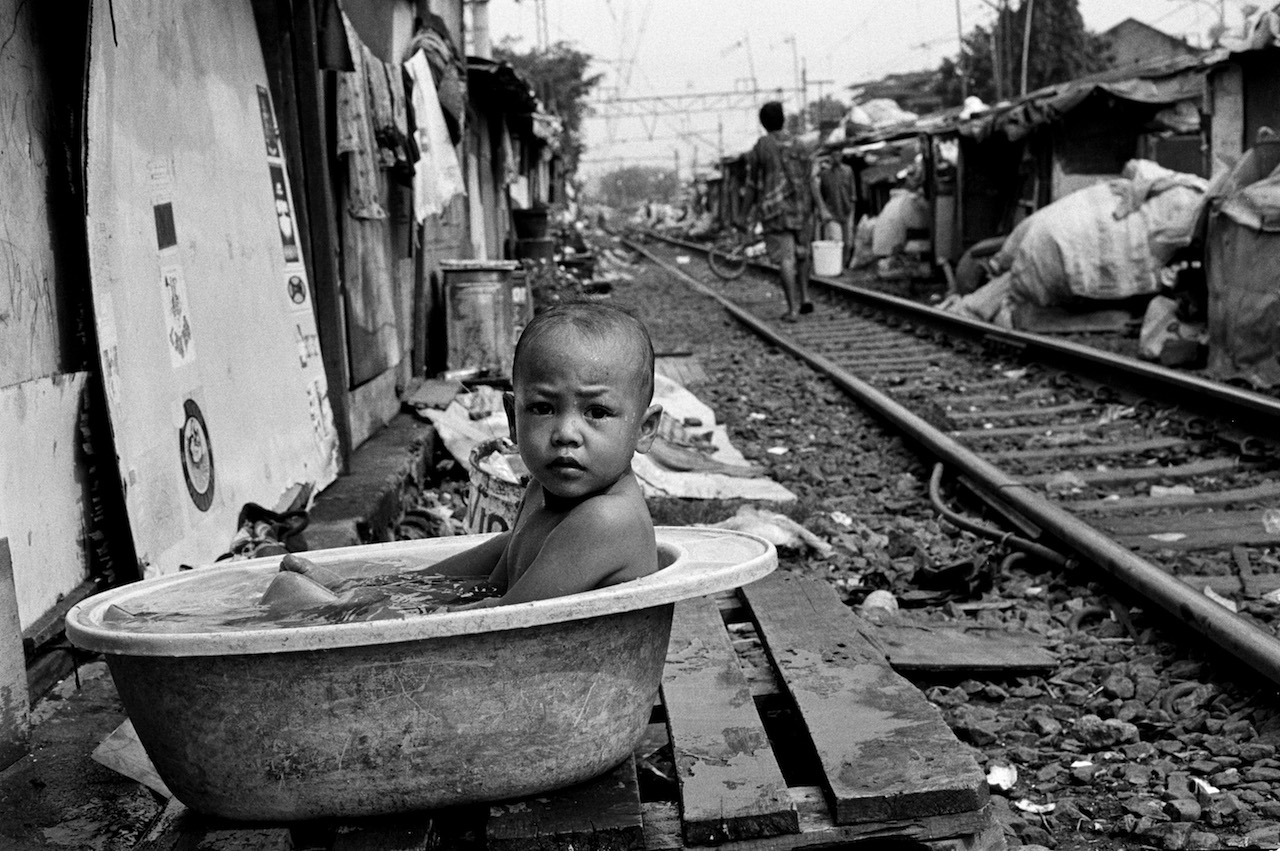

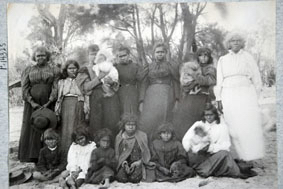

P.14289 – ABORIGINAL CAMP, Pinda Station, Murchison. 1899

At the turn of the twentieth century, we can see from our photographic archives that Aboriginal peoples in Western Australia were in varying stages of transition from their traditional lifestyles into a more regulated westernised existence. As with all archival collections, it is through these surviving images that we begin to understand what life may have been like for those that came before us and the hardships they had to endure to survive in a fast changing world.

As confronting as many of these images can be, it is always important for us as viewers to remember to look past the origins (the purpose of which the photograph was taken) of an image to really “see” the person within it and remember that they were someone’s mother, brother, sister or father.

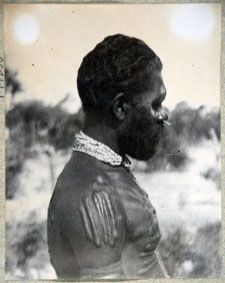

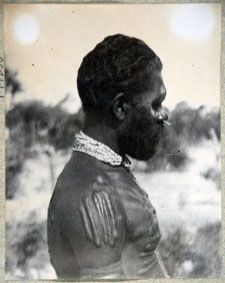

P.14250 – MAN, Broome. Age, 25; Height, 5ft. 91/2in. 1899

As an Indigenous person working with these archives, I often wondered about the person behind the camera and what motivated them to take such photographs in the first place. Whether it was taken for scientific purposes, governmental propaganda or personal curiosity – many of these images – often staged – depict a time and space that categorized Aboriginal peoples as objects and research subjects.

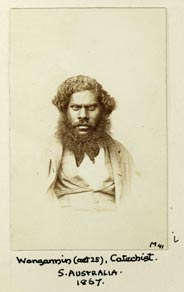

One small collection of images in particular that I have been working with recently originated from the Western Australian Museum founded in 1891 but for reasons unknown were copied to the Cambridge Museum’s collections. As with many archival records from this time period, there is a limited amount of data that can be found with these records. However, we are almost certain that the photographer behind these images was John Thomas Tunney (1870-1929).

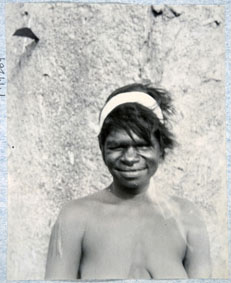

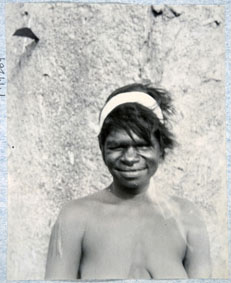

P.14264 – WOMAN, Beagle Bay. Age, 30; Height, 5ft. 2in. 1899

Tunney was employed by the Western Australian Museum from 1895-1906 and was responsible for adding to the Museum’s natural history collections. As part of his employment, he was required to photograph Indigenous peoples in ‘their natural state’ and collect their cultural materials/objects where possible. Throughout his fieldwork Tunney travelled broadly across Western Australia.

You can see that the majority of his photographs are more scientific in nature, however there are the occasional group images that portray Aboriginal people more informally and in a less staged manner.What Tunney’s images highlight is the fact that even though his photographs were taken here in Australia over a century ago, the fact that they -like the rest of our collections- have found a place within an Institution overseas underscores just how much interest European countries had regarding us as a people and culture. Whether it originally stemmed from a research curiosity or a genuine interest to know more about our people, without their involvement we may never have had this opportunity to give back to families’ and communities’ images of their ancestors.

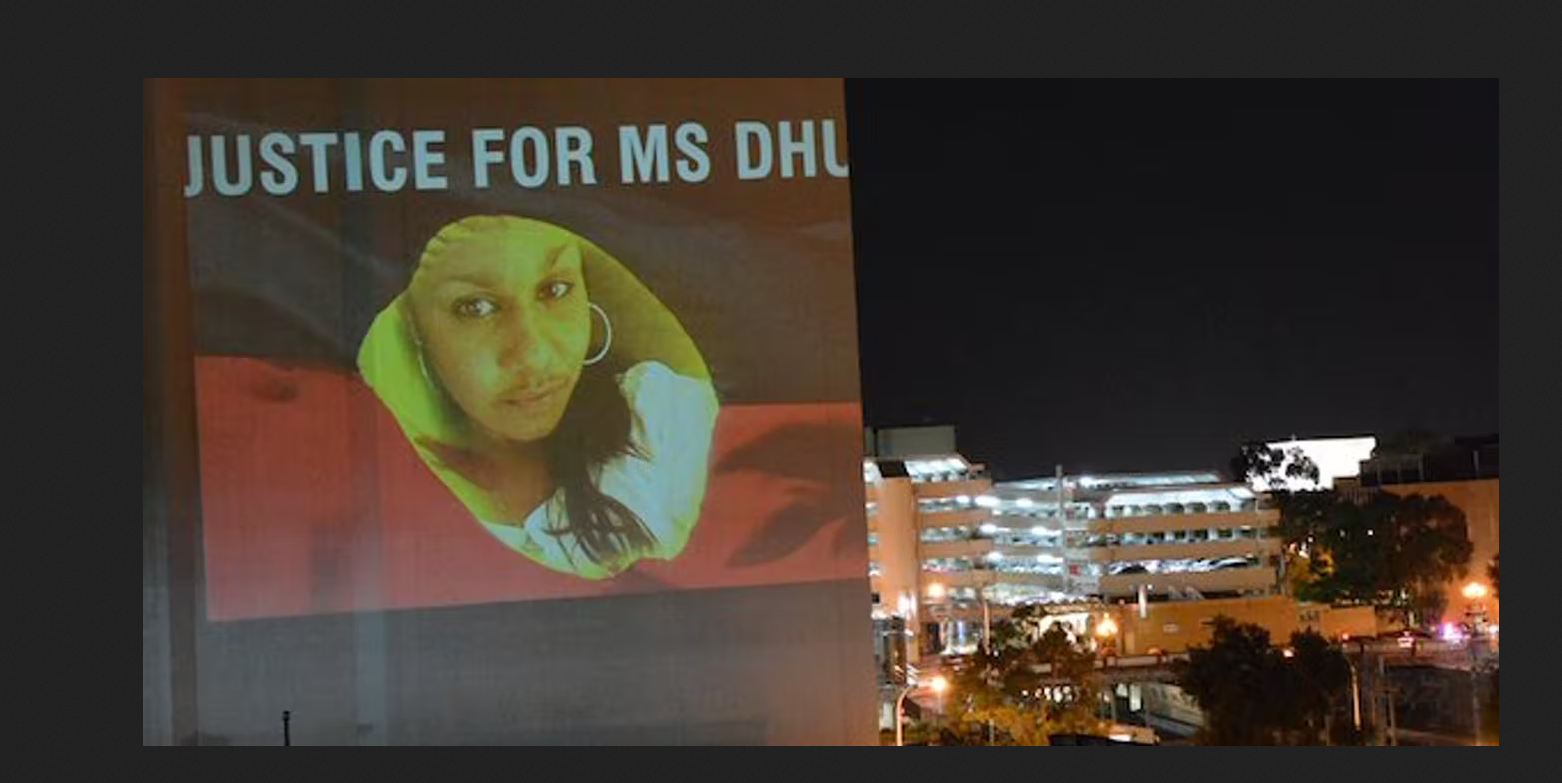

A light graffiti image of Ms Dhu is projected on a building in Perth.

A light graffiti image of Ms Dhu is projected on a building in Perth.