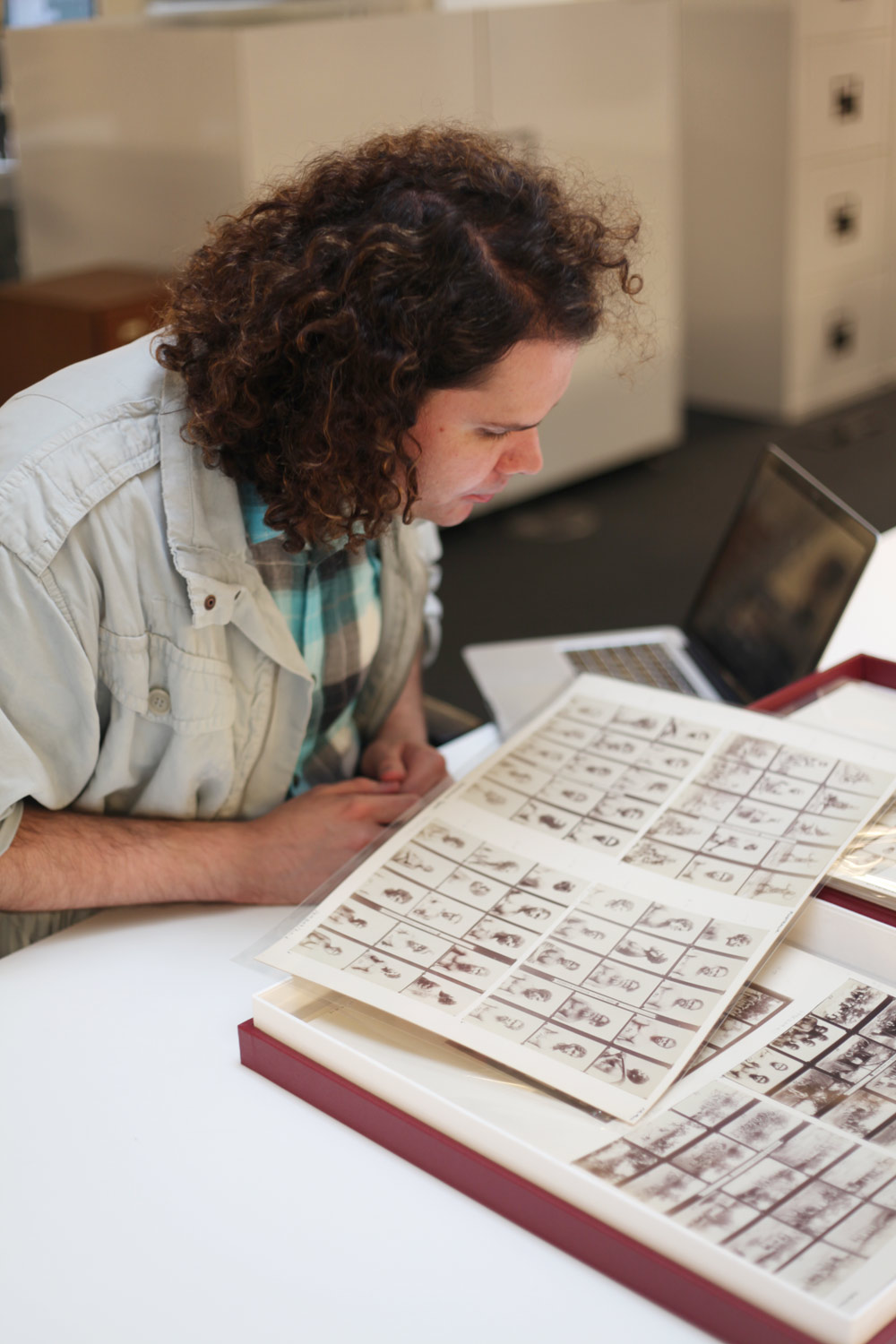

Dr Chris Morton, project partner

When the project began in 2011, indigenous artist Christian Thompson was invited by project partner Dr Chris Morton at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, to collaborate. In particular, Christian was invited to engage with the museum’s historic collection of photographs from Australia and make a new body of work that the museum would exhibit.

The resulting exhibition, We Bury Our Own , opened in Oxford and Melbourne in June 2012 to critical acclaim, and subsequently travelled internationally. This essay discusses some of the themes in the work and its connection to the museum archive.

Over the course of a year, Christian made several research visits to view photographs of Aboriginal people at the Pitt Rivers Museum, mostly dating to the late nineteenth century. The collection itself was built up after the museum’s foundation in 1884 as an anthropological research resource, and the museum’s first Curator, Henry Balfour, used his extensive contacts in Australia, such as close colleague and friend Baldwin Spencer, to build up the archive.

The experience of working with the collection was emotional one for Christian, and for the museum was an innovative collaboration from which we learned a great deal. Although not explicitly quoted in the work made as a result of this engagement, both the experience of looking at the historical images, the modes of representation they carry, and the painful histories they hold, can be understood as lying at the heart of the work. As Christian mentions in the film that he commissioned from Michael Walter to contextualize the work, he turned down my offer of looking through the museum’s collection digitally, and instead preferred to spend time with the original material in the museum, experiencing the way they exist archivally rather than at one remove.

Rather than directly invoking or re-presenting historic imagery, as is evident in the work of other artists such as Brook Andrew (who has also worked extensively with archives), Christian chose to take the history of photographic representation of Aboriginal people as a starting point for the ‘spiritual repatriation’ (see below) of the archive through the redemptive process of self-portraiture. Importantly, this process has not involved drawing on those historical markers of identity which are so prevalent in ethnographic imagery, but rather his own fluid and evolving transcultural identity, as well as biographical markers of another recent identity, that of an Oxford student in formal dress.

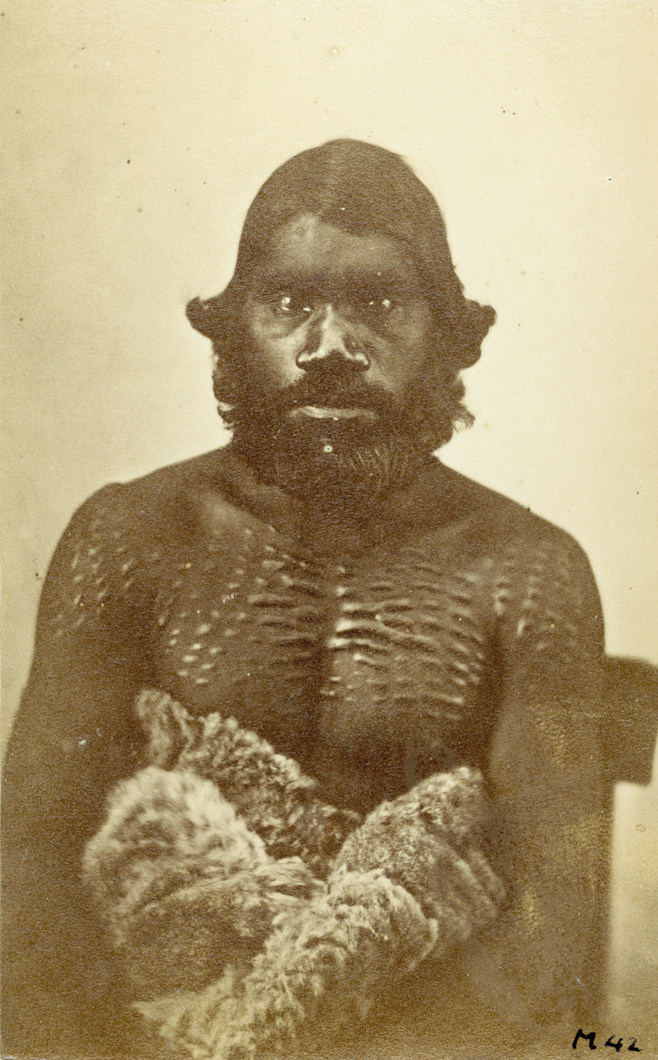

Studio portrait of a man from South Australia, circa 1860. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (1998.249.33.2)

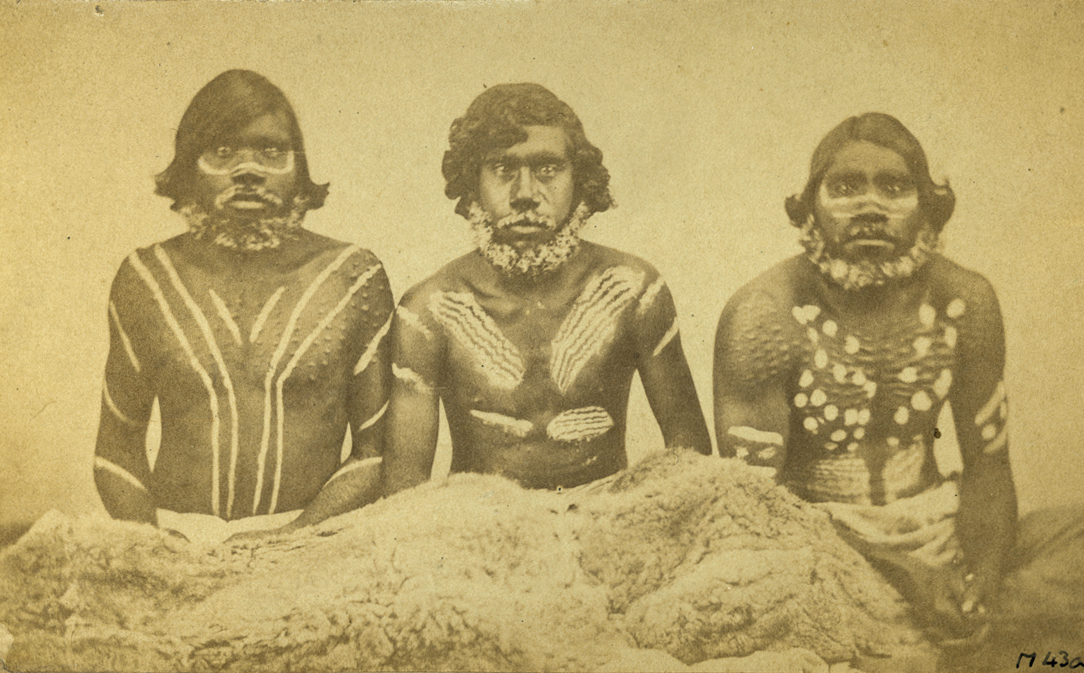

I remember us talking at great length about many of the museum’s photographs, but some stick in my memory as having provoked more of a response from Christian than others. One of them is a portrait of a South Australian indigenous man with a heavily scarified chest, wrapped around the waist by a skin cloak. His hair is parted, and combed down the sides of his head, curling out slightly. The other shows three men (possibly including the same man to right), all with scarifications and body paint, their hair again combed in nineteenth-century fashion. These portraits in the collection had a particular resonance for Christian, and can be felt in the resulting work.

Studio portrait of three men from South Australia, circa 1860. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (1998.249.33.5)

Although archival imagery is an inspiration for Christian generally, he is also inspired by the materiality and composition of a wide variety of images from many different reference points such as contemporary fashion, film, and music. It is this playful blending of genres that not only makes his approach distinctive, it also resonates historically with the blending of scientific and popular genres in the archival imagery with which he engaged during the project.

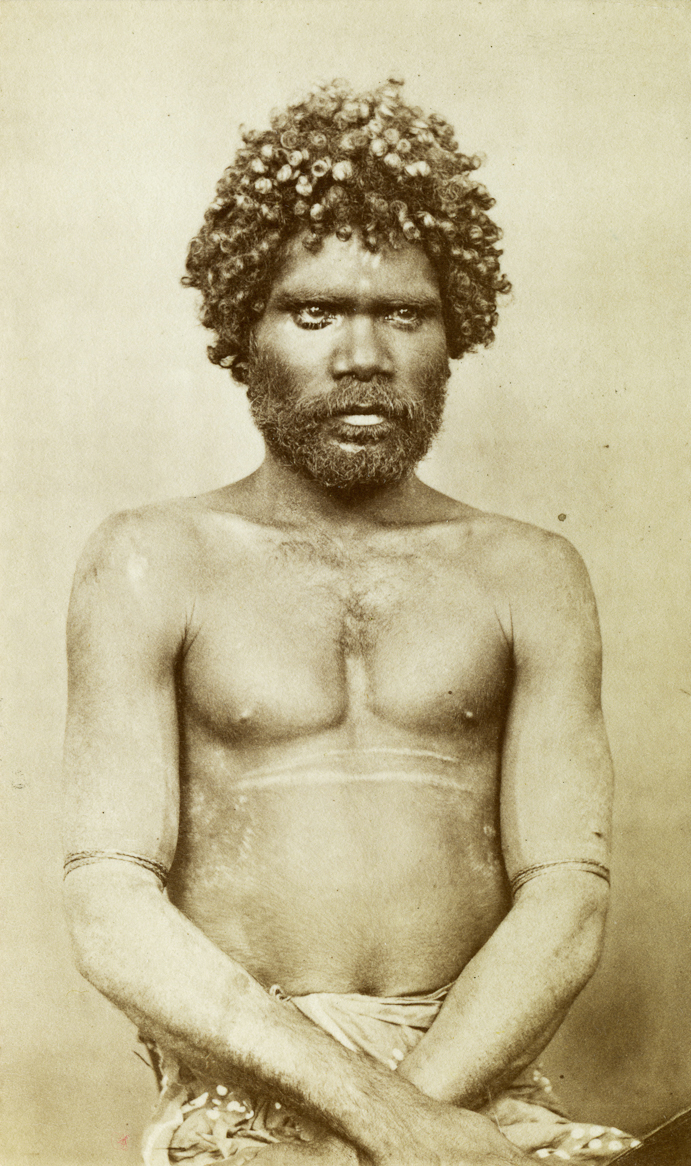

One of the main points of reference to the historical archive in the work is the use of the more scientific end of nineteenth-century ‘ethnographic’ portraiture; head-and-shoulders, full-face, looking directly into the camera, as in the work of policeman Paul Foelsche of Darwin in the 1870s.

Portrait of a Waggite man called Nabbang, 1879. Paul Foelsche, Darwin. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (1998.249.19.10)

As mentioned, one of the most interesting aspects of the collaboration was the exploration of what Christian called the ‘spiritual repatriation’ of the archive through art. Of course, the physical repatriation of Aboriginal human remains is also a process with deep spiritual signicance and resonance to those communities involved in receiving them. But in the case of archives – and in particular photographs – those ancestors held in the images remain in the storerooms of remote institutions even after copies have been returned or shared online.

The reproducibility of the photographic image means that the surface information it holds can easily be shared, especially in the digital age. But the images of ancestors, as ethnographic studies around the world now show us, are more than the chemical traces of light on a surface – they have a direct and spiritual connection to the person photographed, and so hold significant spiritual and emotive qualities. It is this creative tension, between the archive as a permanent ancestral resting place, and yet as a reproducible and dynamic historical resource, that lies at the heart of Christian’s concept of the exhibition space as a spiritual zone.

The scientific scrutiny of the colonial lens is dramatically inverted in We Bury Our Own however, with the indigenous appropriation of the means of representation through the self-portrait, as well as the inversion of a key marker of cultural identity – dress. By wearing Oxford academic dress in the portraits, Christian makes a powerful statement about historical and political processes of identity formation within contemporary Aboriginal communities. As one of the first two Aboriginal students at the University of Oxford, the reference to Oxford in the work is full of historical resonance. Charlie Perkins himself, after all, was the first Aboriginal person to become a university graduate, from the University of Sydney in 1965.

As a significant body of new work by an indigenous artist engaging with a European collection, We Bury Our Own is a major outcome of this project. It even made the cover of the publication Anthropology Today! As the project website is published, and the historic images are made available to indigenous communities, many more creative engagements, appropriations, conversation and repatriations will hopefully take place.